Catoosa endures early years of bloody conflict

Residents care for wounded, search for Union spies

By Randall Franks

While still in its infancy, Catoosa County and its inhabitants were thrust into a mortal conflict that split families and the nation. Since the days of America’s founding fathers, the debate on whether new states and territories should utilize slavery or abolish the practice had simmered like a teapot, and by 1860 the pot was about to blow.

From the Battles of Ringgold Gap and Chickamauga to the hospitals that cared for the wounded to the Great Locomotive Chase, Catoosa County played an integral part in the Civil War.

The ever-present debate over which entity should have control over issues within state boundaries — the state or federal government — loomed large in 1860. These concerns were especially strong in the Southern states among the 13 original colonies. Only 90 years before, each had its own currency and laws to rule its land, and the people answered only to the King of England or his representatives and not to the other colonies.

Two decades before the war, the Cherokees were forcibly removed to Oklahoma.

Settlers came from Virginia, Tennessee, the Carolinas and other parts of Georgia to carve a homestead out of what was considered wilderness, although the Native Americans already operated many productive farms in the area.

While historians may debate for years over the reasons behind the Civil War, whether it was states’ rights or the abolition of slavery, one fact does remain for Catoosa County — its soil hosted some of the bloodiest fighting of the conflict, and many of its inhabitants suffered the loss of family, homes and belongings and endured famine and disease.

Now, 140 years later, folklore of what happened to Catoosa during the conflict between the North and South is still a regular part of tales told around the fireplace or dinner table.

According to William (Bill) H.H. Clark’s “History in Catoosa County,” the county boasted 710 slaves in 1860 — 352 males and 358 females. The county’s population totaled 5,082 in 1860. On Jan. 19, 1861, Georgia joined with other Southern states seceding from the United States of America. Unlike most Southern states with a strong vote in favor of secession and only a handful of legislators against the move, Georgia was more prominently divided, with 208 for secession and 89 against.

Two representatives from Catoosa County voted, with each standing on a different side of the issue.

Joseph T. McConnell, a Ringgold attorney elected as the first state representative from the newly formed Catoosa County in 1853, voted for secession.

Maj. Presley Yates, a prominent landowner whose home still stands at Yates Springs, voted against.

According to Ringgold resident George Hendrix, whose great-great-grandfather, Henry Strickland attended the convention representing Tattnall County, two secession votes were held. On the final vote, many, including his ancestor, changed their votes in favor of seccession.

While McConnell’s name appears on the Ordinance of Secession in favor of the move, Yates does not appear either in favor or against. Why he did not vote the second time is not referenced in local histories.

By April 11, 1861, the Civil War had begun with the Confederate siege on Fort Sumter, S.C.

Initially, hundreds of men from Catoosa signed up to fight for regiments such as Company B, D, and I of the 1st Confederate Regiment Georgia Volunteer Infantry; Company H of the 26th Tennessee Volunteer Infantry; Company F of the 39th Georgia Volunteer Infantry; Company G of the 11th Georgia Volunteer Infantry; and Company K of the 4th Regiment Georgia Cavalry.

Five days after the war began, Company B was guarding the Navy yard at Warrenton, Fla., near Pensacola.

Over the next four years, Catoosa men were scattered to fight in battles such as Bull Run, Gettysburg, Fort Donelson, Pensacola, Vicksburg, Champion Hill, Shiloh, Tullahoma, Chickamauga, Chattanooga, and Atlanta.

In “Catoosa County, Georgia Heritage,” a Civil War diary entry by local resident Robert Magill details the Magill brothers, who joined the army at the same time to stay together and fought the Battle of Champion Hill, Mo.:

“Sat. 16th May, 1863 — 7 a.m., drew some raw beef; were beginning to barbeque it when, just at 8 o’clock, a few cannons were fired near us very unexpectedly. Formed immediately and marched back about two miles: skirmishing began before our lines were formed, and it was soon ascertained that the Federals were moving in on us in heavy force.

“10 a.m., battle opened with great fury on our left; our line was immediately moved to the left in quick time; formed under heavy fire, and in less than five minutes were charged with perhaps two lines of battle.

“The 34th Georgia was on our right, in a very awkward position, and being struck first, and having no support, after one or two volleys, broke and fled in wild confusion. The Federals pressed through the gap and on our front at the same moment. Our boys, seeing this, became panic stricken and in less than 10 minutes the whole brigade was in wildest confusion. With the exception of about 200 men, all efforts to rally the brigade were in vain.

“Having lost all their artillery and about one-fourth of their men killed or captured, and the Yankees triumphant yells in rapid pursuit, whizzing mini-balls and shells exploding in their midst, were not very soothing antidotes to their agitated feelings,” he wrote. “Brother I.L. was seriously wounded in the right breast; called me in the retreat and said ‘I am killed’ but was walking in; just then I was ordered in the line.”

Robert’s post battle search for his brother was in vain, and he would not discover he survived his wound because the mini-ball struck a Bible he carried in his pocket, until he met I.L. on the street in Tunnel Hill after returning from the war.

Serving the Wounded

With fighting spread throughout Tennessee and Kentucky, the Confederates needed sites for wounded soldiers to heal. Locations such as Catoosa and Cherokee Springs, with abundant water supplies, provided good sites. In Ringgold, hospitals sprung up due to the town’s proximity to the railroad.

At the original Catoosa County Courthouse, the Buckner Hospital was established. Other hospitals in Ringgold were the Bragg Hospital at the Craven house, and the Foard and Hill hospitals, whose exact locations are still unknown. Clark cites Confederate medical director Dr. S.H. Stout with the assessment that Catoosa hosted between 1,900-2,200 hospital beds.

Civil War nurse Fannie A. Beers of Pensacola, Fla., served in Ringgold during part of the war. Clark located her book “Memories,” published in 1889.

“The courthouse, one church, a warehouse and stores and hotels were converted into hospitals,” she wrote. “Row after row of beds filled every ward. Upon them lay wrecks of humanity, pale as the dead, with sunken eyes, hollow cheeks and temples and long claw-like hands. Every train brought in squads of just such poor fellows…”

On one cold, wintry night, as snow lay on the ground, Beers and other staff prepared for 200 wounded from the front, but no place was left to put them. The last church not already used as a hospital was seized when the congregation refused to volunteer the facility for a hospital.

Straw was placed on the floor for beds, and the stoves fired up to warm the church.

As the train arrived with the wounded, Beers related, “… there poured through the doors of that little church a train of human misery such as I never saw before or afterward during the war… They came, each revealing some form of acute disease, some tottering, but still on their feet, others borne on stretchers. Exhausted by forced marches over interminable miles of frozen ground or jagged rocks, destitute of rations, discouraged by failure, these poor fellows cast away one burden after another until they had not clothes sufficient to shield them from the chilling blasts of winter.”

Catoosa’s residents assisted the hospitals by rolling bandages, helping with cleaning, laundry and providing food. According to written diaries and journals, in many instances the people gave what they could not spare in hopes someone might do the same for their loved ones elsewhere.

The hospitals remained in Catoosa until the Confederates withdrew. Many of these areas became hospitals for Federal troops as they moved through the area later in the war.

Except for family losses in far-off places and supporting hospitals, Catoosa’s soil remained relatively untouched by the battles of war until the arrival of Andrew’s Raiders in 1862. As the raiders dispersed through the county, one local woman exclaimed with terrible foresight: “Run for God’s sake, the country’s alive with Yankees.”

The Great Locomotive Chase

In April 1862, 22 of 24 men from the 2nd, 21st, and 33rd Ohio regiments infiltrated far behind enemy lines and made their way to Kennesaw, GA.

Two of the men joined the Confederate Army to avoid being captured and did not reach Kennesaw. Under the leadership of James Andrews, Andrew’s Raiders commandeered a train called “The General” and proceeded to speed towards Chattanooga with the intention of destroying bridges and railroad track behind them.

The risky move was part of the Union’s grand battle plan to assist Union Gen. Ormsby M. Mitchell in his push from Shelbyville, Tenn., to Huntsville, Ala., to eliminate the threat of Confederate reinforcements by rail from Atlanta.

Andrews was a Kentucky spy who posed as a blockade-runner smuggling the malaria drug quinine to conceal his activities from Southern authorities.

The group took the train at Big Shanty and managed to get a head start. Conductor W.A. Fuller and Western and Atlantic shop foreman Anthony Murphy chased on foot until they found a hand car and then a train to continue the chase.

With each bit of destruction left by the raiders, they abandoned another vehicle until an alternative was found. Finally in Adairsville, the pair boarded the Texas and followed The General backward up the track.

The General sped by a passenger train at Calhoun carrying Confederate Capt. W.J. Whitsitt of Ringgold of the 1st Confederate Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Whitsitt, who was returning to Mobile, Ala., with recruits from Ringgold and 10 armed soldiers, joined the chase on another train, The Catoosa.

As the raiders heard the sound of the Texas behind them while trying to take up some rails, raider William Pittenger wrote later if it had been, “a thousand thunderclaps (it) couldn’t have startled us more.”

The raiders released boxcars to slow the progress of the Texas, but the train kept going, pushing the boxcars to Resaca where they were left on a sidetrack.

The raiders chugged through Tunnel Hill, hiding their numbers at the depot and reportedly fearful of an ambush at the tunnel. After making it through, they sped towards Ringgold.

Clark relates raider Daniel Dorsey’s story in his book: “After gaining a little in the enemy, who were at times in plain view, we set fire in the last boxcar… The rains had so soaked everything that this seemed impossible and our fire burned aggravatingly slow.”

The group tried to burn the first Chickamauga bridge but was unsuccessful. They also did not destroy bridges over the Etowah River or the tunnel at Tunnel Hill.

The raiders ducked when passing area residents, hoping not to draw attention, but at this point the race was nearly over as the General gave out north of Ringgold, just off Ooltewah-Ringgold Road.

Andrews and his men jumped from the moving train at various points near its final stop and made their way to the forests. Two of the raiders, William Knight and Wilson Brown, remained on the train and put it in reverse before they jumped, sending it towards the Texas.

Almost immediately, the Texas arrived with Capt. Whitsitt and his men close behind.

The railroad men and the soldiers began the foot chase to round up the spies. Many of Catoosa’s residents joined in the search.

Raider Jacob Parrott was one of those captured and brought to Ringgold. Clark shared in his book Parrott’s account of his capture:

“Sam Robertson and I took to the woods together. After a time, we came out of the woods. We came out on the railroad; there were four citizens there who saw us and took us. We were taken to Ringgold.

“An officer and four soldiers took me out and stripped me, bent me over a stone and whipped me. He gave me 100 lashes with a strip of rawhide. He stopped three times during the whipping, let me up and asked me if I would tell, and when I refused to do so he would put me down and whip me again.”

Confederate authorities and citizens eventually caught Andrews and his men. Some of them made their way as far as Bridgeport, Ala.

Most of the group went to Confederate prisons. Eight raiders escaped and six received paroles.

The Confederate authorities hanged Andrews and seven of his men on June 7, 1862, and buried them in unmarked graves. Their remains were later moved to the Chattanooga National Cemetery.

Congress created the Medal of Honor in 1862, and awarded it to 19 of the Raiders. Parrott later was the first soldier to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Andrews, as a civilian, was not eligible.

The General survived, serving the Western and Atlantic and the Louisville and Nashville railroads for another 30 years.

Disney produced a film, “The Great Locomotive Chase,” in 1956 starring Fess Parker as Andrews. The story was also the basis for Buster Keaton’s film “The General.”

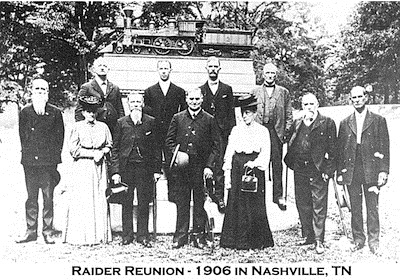

Andrew’s Raiders and family gather in 1906 for a reunion in Nashville, Tenn. From left, front, are John Reed Porter, Mrs. Knight, William Knight, Mr. and Mrs. Jacob Parrott, Daniel Dorsey and “Texas” Fireman Henry Haney; (back) William Bensinger, William Fuller, Charles Bensinger and Anthony Murphy. (Photos of the participants in the Great Locomotive Chase from "The General & The Texas: A Pictorial History of the Andrews Raid, April 12, 1862." Used by permission ©1999 by Stan B. Cohen and James G. Bogle.